Mothers experiencing low milk supply often receive unsolicited advice like “Perhaps you need to put in more effort,” “Have you considered fenugreek supplements?” or “Maybe you’re not hydrating enough.”

These suggestions, though well-intentioned, frequently come from friends, family, or even breastfeeding advocates who may overlook underlying medical complexities. While most lactation challenges can be resolved through improved breastfeeding techniques, some mothers face a physiological barrier: primary lactation failure. This condition occurs when a mother’s body cannot produce sufficient milk despite optimal breastfeeding practices—proper latch, frequent feeding, uninterrupted mother-baby bonding, and no anatomical issues like tongue-tie or cleft palate.

Primary lactation failure may stem from multiple causes. These include prior breast or chest surgeries that damage nerves or milk ducts, hormonal imbalances linked to conditions such as polycystic ovary syndrome or thyroid disorders, and underdevelopment of mammary tissue during puberty. In plastic surgery literature, this underdevelopment is termed “tubular breast deformity,” historically viewed as a cosmetic concern with corrective procedures focusing on appearance rather than preserving or restoring lactation function.

As breastfeeding gains recognition as a public health priority, more mothers aspire to breastfeed. However, systemic gaps persist in understanding and addressing lactation failure. Limited clinical guidance exists for those with hypoplasia/insufficient glandular tissue (IGT), leaving many families without evidence-based solutions. This highlights the urgent need for enhanced medical education, targeted prenatal screening, and specialized interventions to support these mothers in achieving their feeding goals.

Why Can’t Some Mothers Produce Milk?

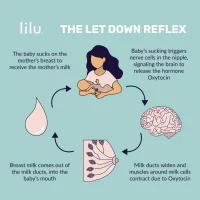

Lactation failure is broadly categorized into three types: preglandular, glandular, and postglandular (Morton, 1994). Preglandular causes, such as hormonal imbalances from retained placental tissue or postpartum thyroiditis, directly disrupt milk synthesis. Postglandular factors emerge after birth and involve challenges like poor breastfeeding initiation—such as ineffective milk transfer due to infant difficulties or suboptimal practices like scheduled feedings and prolonged mother-baby separation. Glandular issues, including prior breast surgery or hypoplasia/insufficient glandular tissue (IGT), reflect physical limitations in milk-producing tissue. These categories often overlap, with glandular insufficiency frequently compounded by preglandular or postglandular contributors. Proactive measures, such as understanding personal health history, discussing pre-conception medications with providers, and maintaining a healthy pre-pregnancy BMI, can optimize hormonal balance and support lactation potential.

Do I Have Hypoplasia/Insufficient Glandular Tissue?

Hypoplastic breasts can vary in size—small or large—but the defining features lie in shape, positioning, and asymmetry rather than volume alone. Even breasts of typical size may lack functional glandular tissue, relying instead on fatty tissue to fill the breast contour.

Research by Huggins, Petok, & Mireles (2000) involving 34 mothers identified physical traits linked to reduced milk production:

- Wide spacing between breasts (more than 1.5 inches apart)

- Breast asymmetry (significant size disparity between sides)

- Stretch marks on breasts without prior growth during puberty or pregnancy

- Tubular breast morphology (resembling an “empty sac”)

Additional indicators may include:

- Disproportionately large or bulbous areolae

- Absence of breast changes during pregnancy, postpartum, or both

Many with IGT recall feeling their breasts were “unusual” during adolescence, yet diagnosis often occurs later—during pregnancy when breasts show minimal growth (“the booby fairy doesn’t arrive”) or postpartum when milk supply is insufficient. Exceptions include individuals who previously sought breast augmentation, where terms like “tuberous breast deformity” or “constricted breast” (used in plastic surgery) might have signaled underlying hypoplasia/IGT.

Notably, some mothers with these physical markers still achieve a full milk supply. However, prenatal identification of hypoplasia/IGT traits warrants proactive breastfeeding support to optimize outcomes. A lack of breast changes during pregnancy may also signal potential challenges, emphasizing the value of early assessment and tailored care.

Why Can’t I Produce Enough Milk?

When glandular-related lactation failure is suspected, it’s critical to first evaluate and exclude preglandular (e.g., hormonal imbalances) and postglandular causes (e.g., breastfeeding practices). For mothers with confirmed hypoplasia/insufficient glandular tissue (IGT), repeated questions like “Have you tried [specific remedy]?” can feel dismissive. However, healthcare providers often ask these to rule out more common—and often fixable—causes of low milk supply. A more collaborative approach, such as asking, “What strategies have you explored, and what other factors might contribute?” respects the mother’s experience while systematically addressing potential issues.

Research suggests prenatal exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals like dioxins (from maternal body burdens) may impair breast development during critical growth phases like adolescence and pregnancy. Even when breast growth occurs, it might be asymmetrical or dominated by fatty tissue rather than functional glandular tissue—a pattern linked to hormonal disorders such as polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), thyroid dysfunction, or insulin resistance. Some individuals with IGT also report luteal phase defects, marked by inadequate progesterone levels post-ovulation, subtle basal body temperature shifts, and premenstrual spotting. These hormonal imbalances not hinder glandular tissue development but may also impair its milk-producing capacity. Addressing these irregularities through medications or herbal supplements could optimize existing glandular function, though responses vary widely and require further study.

The interplay of environmental, developmental, and endocrine factors underscores the need for personalized care. While some mothers with hypoplastic breast traits achieve full milk supplies, prenatal identification of IGT markers warrants proactive lactation support to mitigate risks.

What Options Do I Have Now? I Deeply Wanted to Breastfeed My Baby.

For mothers facing breastfeeding challenges, it’s crucial to acknowledge both emotional and practical dimensions. While some find peace in transitioning to bottle-feeding with warmth and responsiveness, others grieve the loss of their envisioned breastfeeding journey—particularly those concerned about the health implications of not providing human milk. Before exploring solutions, ensure all potential breastfeeding barriers (e.g., latch issues, feeding schedules) are addressed, as unresolved factors can undermine efforts to boost milk production. Connecting with breastfeeding support groups or experienced mothers can provide reassurance about normal infant behaviors, such as frequent feeds or fussiness, which are common even in full-supply scenarios.

Adaptive Feeding Strategies

Mothers with hypoplasia/IGT may use at-breast supplementing tools—thin tubes attached to the nipple connected to pumped milk, donor milk, or formula—to maintain breastfeeding while ensuring adequate nutrition. Others combine partial breastfeeding with galactagogues (milk-boosting herbs/medications) and targeted supplementation. For instance, offering a small bottle first to ease hunger, then transitioning to the breast, can balance infant needs with maternal comfort. Around 6 months, nutrient-dense solids (e.g., avocado, sweet potato) may reduce reliance on supplements, as they provide higher calories per ounce than formula. Collaborate with your pediatrician to tailor a plan based on your baby’s growth and needs.

Emotional Healing and Personalized Support

Allow yourself space to mourn unmet expectations while identifying what aspects of breastfeeding matter most to you—whether nurturing closeness or providing antibodies. Seek guidance from an IBCLC (International Board-Certified Lactation Consultant) experienced in low-supply cases. They can help navigate options like pumping, supplementing tools, or donor milk, aligning strategies with your comfort level and goals. Open communication about your priorities (e.g., “I want to maximize my own milk output” or “I need help using this device”) enables them to create a realistic, sustainable care plan.

Redefining Success

Many mothers discover that breastfeeding fulfillment extends beyond milk volume—encompassing bonding, immune support, and shared nourishment. With tailored support, even partial breastfeeding combined with supplements can create a meaningful, resilient feeding relationship. As one mother shared, “The journey taught me flexibility and deepened my connection with my baby, regardless of ounces produced”.