Responsive caregiving—characterized by timely and attuned responses to an infant’s signals—is a well-established protective factor for infant health, cognitive development, and emotional stability. Secure attachment bonds formed through consistent caregiver responsiveness lay the foundation for lifelong social competence, academic achievement, and psychological resilience.

Central to this framework is responsive feeding, a dynamic process where caregivers interpret and act on hunger/satiety cues during breastfeeding or bottle-feeding. This practice preserves infants’ innate caloric self-regulation—a capacity that diminishes with age if unsupported. By allowing infants to initiate and terminate feeds based on internal cues, caregivers reinforce metabolic autonomy while fostering trust in caregiving relationships.

Mechanisms of Responsive Feeding

- Biological Synchronization: Infants’ frequent feeding patterns (common in breastfeeding) stimulate prolactin surges, optimizing milk production and infant growth trajectories.

- Behavioral Anchoring: Early responsiveness to cues like rooting or hand-sucking prevents overfeeding risks and establishes lifelong eating competence.

- Developmental Safeguards: Studies link responsive feeding to reduced childhood obesity rates and enhanced self-regulation skills, as infants learn to associate bodily signals with appropriate actions.

Addressing Parental Concerns

While caregivers often worry about:

- Perceived feeding frequency (e.g., “Is my breastfed infant getting enough?”)

- Schedule-driven expectations (e.g., rigid feeding intervals)

Evidence confirms that demand-led feeding aligns with physiological needs. Breastfed infants naturally cluster-feed during growth spurts, which boosts milk supply without indicating insufficiency. Tools like growth charts and diaper output monitoring can alleviate anxiety about intake visibility.

Clinical Implications

- Milk Supply Optimization: Responsiveness during the first 6 postpartum weeks critically shapes lactation capacity.

- Cultural Adaptation: Balancing traditional feeding practices with evidence-based responsiveness requires culturally sensitive guidance.

This approach transforms feeding from a transactional act into a developmental dialogue, where each interaction strengthens both nutritional and relational outcomes.

Breastfeeding Frequency in Infants: Patterns and Influencing Factors

Infant feeding frequency exhibits considerable individual variation, though research indicates most newborns breastfeed 8–12 times daily, with some exceeding 18 sessions in 24 hours. Longitudinal studies note a tendency toward the upper end of this range, averaging 11–12 feeds per day during early infancy.

While caloric requirements stabilize after the first weeks, infants gradually develop the capacity for larger-volume feeds. By 8–12 weeks, some transition to longer intervals between sessions. However, this progression often reverses around 4 months, coinciding with developmental growth spurts that temporarily increase feeding frequency—a pattern sometimes misinterpreted as readiness for solid foods. Individual preferences persist throughout infancy, with some infants maintaining frequent “grazing” patterns even after starting solids, mirroring adult eating style diversity.

Natural feeding rhythms rarely conform to rigid schedules. Responsive feeding—allowing infants to initiate sessions based on hunger cues—aligns with biological programming. Cluster feeding (repeated short sessions over hours) serves as an evolutionary adaptation to boost maternal milk production during growth phases.

Milk composition significantly influences feeding behavior. Mothers with higher-fat breastmilk often observe shorter, more efficient feeding sessions compared to those with lower-fat milk. Additionally, fat concentration escalates during individual feeds and peaks in daytime milk. Environmental factors like heat may reduce milk energy density, prompting compensatory increased intake frequency.

Cultural practices profoundly shape feeding patterns. Western norms emphasizing maternal-infant separation contrast with hunter-gatherer societies like the !Kung, where infants average four hourly feeds of ≤2 minutes. Observational studies reveal:

- Rural Thai infants average 15 daily feeds

- UK co-sleeping infants demonstrate elevated nighttime nursing frequency

These disparities highlight how accessibility—facilitated by babywearing and co-sleeping—naturally increases feeding opportunities compared to scheduled Western approaches.

Physiological Factors Underlying Frequent Infant Breastfeeding Patterns

Breastmilk’s composition—characterized by lower fat content yet higher concentrations of easily digestible carbohydrates like lactose—facilitates rapid gastric emptying. This metabolic efficiency explains why breastfed infants typically require feeding every 2 hours, compared to the 3-hour intervals common among formula-fed infants. Studies confirm that 75% of breastfed newborns return to a fasting metabolic state within 3 hours post-feeding, whereas only 17% of formula-fed infants achieve this threshold within the same timeframe.

Infant gastric capacity further influences feeding rhythms. With a maximum stomach volume of 90ml, breastfed babies often consume smaller quantities per session, rarely filling their stomachs completely. To meet daily nutritional requirements (~750ml in the first six months), frequent feedings become biologically necessary even at maximum intake capacity. In contrast, formula-fed infants exhibit significantly higher milk consumption patterns, ingesting double the volume on day one and triple by day two compared to breastfed counterparts.

This physiological interplay between milk composition, digestive kinetics, and gastric limitations creates an evolutionary adaptation ensuring optimal nutrient absorption while supporting lactation regulation through frequent mammary stimulation.

The Importance of Responsive Feeding in Infant Health and Development

Adapting to the irregular feeding patterns of breastfed infants can be demanding, often leading mothers to discontinue breastfeeding due to concerns about adequacy or the perceived convenience of formula schedules. However, responsive feeding—aligning feeding practices with a baby’s cues—is biologically essential and offers multifaceted benefits.

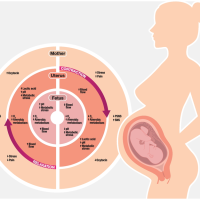

Responsive feeding directly supports lactation dynamics. While breastmilk production begins minimally during pregnancy, hormonal shifts involving prolactin and oxytocin trigger a surge postpartum. Sustaining this supply relies on frequent milk removal, as the body calibrates production to match demand. Studies demonstrate that infants fed on demand consume 30% more milk than those on rigid schedules, reinforcing the principle that milk synthesis adapts to the baby’s needs.

By optimizing milk supply, responsive feeding accelerates the transition to mature milk post-birth, aids faster recovery of birth weight, and reduces jaundice risks. Conversely, early formula supplementation or pacifier use disrupts natural feeding rhythms, potentially lowering milk intake by up to 30 minutes daily—equivalent to missing a full feeding session. Such interventions may inadvertently reduce lactation efficiency, creating a cycle of perceived low supply and feeding difficulties.

Infants fed responsively exhibit stronger breastfeeding continuity, as this approach fosters trust in hunger and satiety signals. Parent-led routines, conversely, correlate with earlier breastfeeding cessation, often due to complications like latch pain or fussiness—side effects of insufficient milk removal. Responsive feeding also extends beyond nutrition, promoting cognitive and emotional development through consistent caregiver-child interaction.

Globally, practices like co-sleeping and babywearing—common in hunter-gatherer societies—enable frequent, brief feeds (e.g., the !Kung tribe’s average of four hourly feeds). These patterns align with biological norms, contrasting with Western schedules that limit breastfeeding access. Research underscores that responsive feeding not only meets nutritional needs but also strengthens parent-infant bonds, laying groundwork for healthy eating behaviors long-term.

The Biological Imperative of Nighttime Infant Feeding

Infant nutritional and physiological requirements persist regardless of daylight hours. Nighttime feeding remains essential, as breastmilk’s digestibility and infant gastric capacity remain constant after dark. Studies indicate circadian rhythms regulating sleep-wake cycles only begin stabilizing around two months of age, meaning extended nighttime sleep is neither biologically typical nor developmentally expected for newborns.

Cultural narratives often promote unrealistic expectations of infants “sleeping through the night” within weeks—a notion contradicted by both infant physiology and adult sleep patterns. Approximately one-third of adults experience insomnia, raising questions about why society pressures infants to achieve uninterrupted sleep when even mature humans struggle.

Night awakenings serve protective biological functions. Proximity to caregivers during sleep helps regulate infant body temperature, stabilize heart rates, and reduce risks of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). Research associates deeper infant sleep patterns with higher SIDS incidence, suggesting frequent waking may enhance safety.

From a lactation perspective, nighttime nursing critically sustains milk production. Approximately 30% of daily milk intake occurs nocturnally, rising to 50% in cultures practicing co-sleeping. Night feeds stimulate prolactin surges—peak hormone levels naturally occurring after dark—thereby optimizing milk synthesis. This hormonal interplay also supports the Lactational Amenorrhea Method, providing 98% contraceptive efficacy when combined with exclusive breastfeeding.

Comparative studies reveal formula-fed infants may initially sleep longer stretches, though this difference diminishes by 6–12 months. Notably, breastfeeding mothers often achieve comparable total sleep duration despite nighttime feeds, as breastfeeding facilitates quicker resettling.

Sleep training interventions aimed at reducing night feeds frequently undermine breastfeeding continuity. Responsive feeding aligns with biological norms observed globally—infants in co-sleeping cultures typically nurse 4+ times nightly—while supporting healthy weight gain and long-term feeding behaviors.

Societal emphasis should shift from enforcing rigid routines to supporting parental well-being through community resources and evidence-based education. Recognizing nighttime feeding as developmentally appropriate—rather than a “problem” to solve—could alleviate unnecessary parental stress and promote healthier infant care practices.